As the sell-off in the emerging markets spread in the summer, questions were starting to be asked on whether the next financial crisis is just around the corner. “Are we gonna party like it’s 1997,” wrote Paul Krugman, the Nobel laureate economist who foreshadowed the meltdown in Asia more than two decades ago.

Krugman isn’t saying that a crisis is a certainty. But he tweeted in May 2018 that “it’s become at least possible to envision a classic 1997-8 style self-reinforcing crisis: emerging market currency falls, causing corporate debt to blow up, causing stress on the economy, causing further fall in the currency”.

With the likes of the Indonesian rupiah falling to a near 20-year low against the US dollar, the Philippine peso hovering at a 13-year trough, the Chinese renminbi touching the lowest rate since end of 2016 and the Indian rupee hitting a record of 72.97, it is not difficult to see the pattern becoming evident.

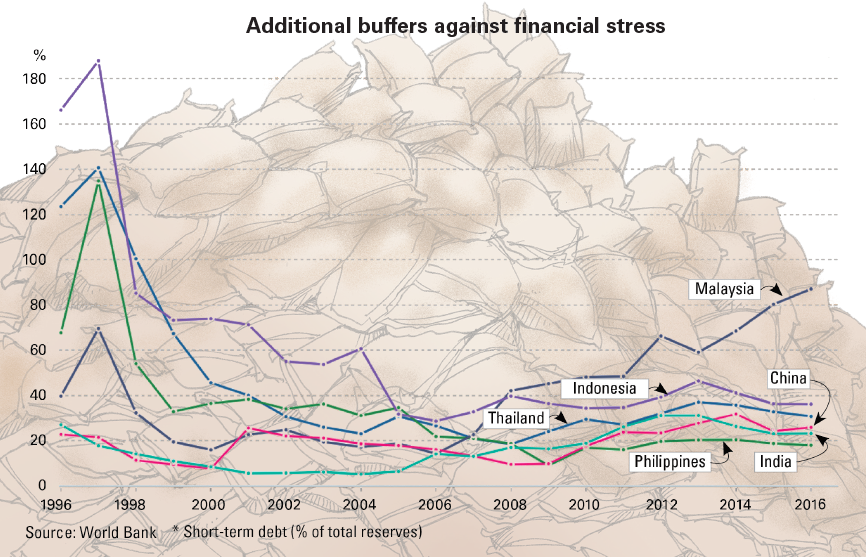

Macroeconomic indicators in emerging Asia, however, are different this time. For example, the level of foreign exchange reserves these countries held were at historic highs until recently. Nevertheless, China still possesses over US$3 trillion in reserves; Thailand’s stands at over US$204 billion; Indonesia at US$118 billion; Malaysia at US$104 billion; and the Philippines at US$77 billion.

Banks, which were at the centre of the Asian crisis in 1997, are far better capitalized in 2018 with many exceeding the international Basel III norms. The tier-one ratio of banks in Indonesia is at over 20%. It is 12.2% in the Philippines and over 14% in Thailand.

What’s also different this time, coincidentally, is the recent changing of the guard at the top of the region’s central banks. This year alone China, Indonesia and Malaysia appointed new governors.

Yi Gang assumed the top job at the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) on March 19 following the retirement of Zhou Xiaochuan, the longest-serving head of the Chinese central bank. Perry Warjiyo assumed the top job at Bank Indonesia on May 24 with the retirement of Agus Martowardojo, while Nor Shamsiah Yunus became governor of Bank Negara Malaysia on July 1, replacing Muhammad Ibrahim who had resigned.

The Philippines also appointed a new central bank governor a year ago on July 3 when Nestor Espenilla Jr was chosen to take over from Amando Tetangco Jr, who retired after heading the bank for 12 years, the first governor of the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas to serve two terms.

Although having been at the helm of their central banks for a few years, the governors in Vietnam and Thailand stand out for their youth. Le Minh Hung, governor of State Bank of Vietnam became the youngest governor in the history of the State Bank of Vietnam when he was appointed in 2016, aged just 46. In Thailand, Veerathai Santiprabhob was appointed to become governor of the Bank of Thailand three years ago when he was 45, the youngest in four decades.

While the basic economic health of a country counts for sure, the perceived credibility of the central bank governor matters especially in being decisive and in managing expectation. In a crisis situation, when sentiment often trumps fundamentals, the value of a central banker’s ability to calm markets and restore order cannot be underestimated.

It was therefore somewhat of a baptism of fire for Indonesia’s Perry when just days after assuming office he had to swing into action by holding an unscheduled board meeting to raise the policy rate to 4.75%. He is not stopping at just using rate hikes to stem the fall of the local currency. More recently, the central bank also unveiled hedging tools to help corporates to manage their foreign currency exposure.

Growth vs stability

The outflow of funds from the emerging markets is happening even as governments in the region are accelerating their long overdue infrastructure build-out. This has caused the current account to turn negative in countries such as Indonesia and the Philippines as the imports of capital goods surge.

It is a difficult balancing act of aspiring for sustainable growth while maintaining stability, which Espenilla of the BSP shares with The Asset recently in an exclusive interview. “We are dealing with challenges of looking to the long-term and then managing the short-term. It cannot be denied that the Philippines needs infrastructure badly. If you want to move forward, we need infrastructure. If you don’t undertake investments, both in physical assets – highways, roads, bridges – and investments in human capital – education, health, nutrition, training – the most it will be is the potential 6.7%. If we push any harder, you will have overheating issues. The country needs to grow by more than 7% – 7% to 8% – for a long time so that we will be able to catch up with our neighbours.” (see page 18 for the interview)

Indeed, with inflation spiking up to 6.4% in the latest August reading in the Philippines, which is well above the inflation range set by the BSP of between 2% and 4%, Espenilla is facing pressure and will need to hike rates further. This will be on top of the 100bp since the start of 2018 — including the 50bp hike in August, the biggest quantum in ten years. This could have a consequential impact on cost of funds and therefore the pace of growth.

As the uncertain market outlook tests the mettle of this new batch of central bank governors to navigate the choppy waters ahead, many, however, come with considerable experience of the last crisis. Thailand’s Veerathai, for example, was deep in the trenches when he took leave as an economist at the International Monetary Fund in Washington DC 20 years ago to return home and lead the Policy Research Institute under the Ministry of Finance during the Asian financial crisis when Thailand was the epicentre of the unfolding drama.

Now leading the central bank, Veerathai recently shared the challenges of policymaking. “The turning point of macroeconomic policy stance is not a straightforward one,” he relates during his talk at an event organized by the Stock Exchange of Thailand at the end of August. “Imagine yourself on a road trip with a group of friends. You were driving and one of your friends asked you, ‘when will we make a turn?’ If you have a GPS navigator or open up Google maps, you might be able to say with precision, ‘in 2.5 kilometres’. When talking about a policy course, the answer might be, ‘In the next two or three quarters, if things go according to plan.’ In real life, we policymakers do not have the luxury of having a GPS navigator, not to mention the fact that this said turn could be moved closer or further away without giving any warnings in this volatile world.”

Volatility is being created by several flash points that threaten to dislocate the pace of growth of the past few years. The two most obvious ones are the end of quantitative easing that has led to US rate hikes and the flow of US dollar liquidity out of the region and the uncertain but escalating trade war between China and US that is expected to spill over to the smaller economies in Asia. Other issues bubbling in the background are the inflated asset prices as a result of the chase for yield, the system’s leverage and the political outlook with forthcoming elections in the next 12 months in Thailand, Indonesia and the Philippines.

Any one of these factors could threaten financial stability. Veerathai, for example, notes that the search for yield per se is all well and good if investors are well-informed and manage risks accordingly. “However, we cannot deny that some investors are underpricing the associated risks.” He notes debt accumulation among households, large expansion of foreign investment funds with high concentration in some emerging economies, saving cooperatives’ growing asset base, maturity mismatch of corporate borrowers and rapid growth of unrated bonds are some examples of the issues the central bank has been monitoring over the years.

In the case of the Philippines, Espenilla says the central bank is constantly watching the level of indebtedness at the individual and at the corporate level. He explains: “It is important that we, for example, maintain a policy of flexible exchange rate. The danger with presenting a seemingly stable exchange rate and making implicit promises that the rate will stay there forever encourages corporates, for example, to borrow overseas, tempted by very low rates, and then down the road when the exchange rate is repriced suddenly finding themselves in trouble again, which is an Asian financial crisis lesson.”

“We believe that it is part of good policy to signal to the market that there is volatility in the exchange rate and you have to price that in and include that in your business calculus of what you should or should not do. That has led to a situation where corporates are more prudent in borrowing options. Of course, there are borrowings offshore but you’ve got to match that to offshore sources of income. You see many corporates that are borrowing offshore also investing offshore and generating offshore revenues to hedge their position,” he adds.

Mindful of the potential flash points, however, the central bankers in the region are nevertheless forging ahead to implement structural reforms and use technology to promote financial inclusion. This is one area that countries such as Singapore, Thailand, Indonesia and the Philippines are undertaking using the success of China in applying technology to support a broad-based growth.

How this set of governors perform when the next crisis shakes the economic foundation of this region, only time will tell. Zhu Min, the former deputy managing director of the IMF and a former central banker at the PBoC, believes there is no foolproof approach to preventing a crisis.

“Of course, measures like keeping external debt low, maintaining flexible exchange rates, and implementing smart macro prudential policies can help to stave off disaster,” writes Zhu in a recent article published by Project Syndicate.

“So can the elusive set of policies that are supposed to show credibility and keep markets confident, summoning the ‘confidence fairy’, as Paul Krugman would say. But, just as a virus can afflict the healthiest of people, a crisis can sweep up even a well-prepared economy. That is why countries must look beyond preventive measures and strengthen their ability to support a speedy recovery,” Zhu adds.

.jpg)

.jpg)