Closing the global infrastructure investment gap is a thorny problem. Estimates vary as to the size of the gap. But the numbers are enormous. Management consultant McKinsey & Co estimates that US$3.3 trillion of infrastructure investment is required annually to support global growth. Emerging economies will account for some 60% of that demand.

Developing Asia alone will need to invest more than US$1.7 trillion in infrastructure each year until 2030 to maintain its own growth momentum, tackle poverty, and respond to climate change, according to the Asian Development Bank report released in February. McKinsey concludes that if the current level of underinvestment continues, there will be a yearly shortfall of US$350 billion. But the size of that gap triples if you include the additional investment required to reach the United Nations’ sustainable development goals. That puts the total gap to more than US$1 trillion a year.

Yet government spending on infrastructure projects has been decreasing in most countries as public sector balance sheets have come under increasing strain. Likewise, a tighter regulatory environment has resulted in a drop-off in financing from the banking sector, the traditional source of private sector funding for infrastructure.

Yet government spending on infrastructure projects has been decreasing in most countries as public sector balance sheets have come under increasing strain. Likewise, a tighter regulatory environment has resulted in a drop-off in financing from the banking sector, the traditional source of private sector funding for infrastructure.That said, the challenge has never been due to insufficient investment funds. There is supposedly over US$90 trillion waiting to be put to work by the likes of pension funds, insurance companies and asset managers. The solution to filling the infrastructure gap is to create an environment where asset managers feel comfortable in committing long-term capital into long-term infrastructure projects.

The obligation to nurture that environment falls into the lap of policymakers and their conduits.

“The scale of the sustainable development challenge is huge,” says Andrew Davison, senior vice president at Moody’s Investor Services. “Technical assistance, risk mitigation and credit enhancements from the multilateral development banks (MDBs) will play an important role in facilitating investment in emerging market infrastructure by institutional investors.”

That sentiment is echoed within the MDBs. “There is a willingness within institutional investors to invest in emerging markets, but that willingness is not reflected in actuality,” says Thomas Maier, managing director for infrastructure at the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD). “It is our task to understand the problems constraining investment and then to address those issues.”

Long-term lunch

Long-term lunch There has been an increase in appetite for infrastructure debt from institutional investors in the developed markets, however. In the current low interest rate environment, exposure to infrastructure projects provides a means of matching long-term assets to equivalent liabilities, diversification to portfolios and returns that could not be equalled in the bond markets.

Changes in European regulations have also reduced capital charges for insurers on qualifying infrastructure investment and that has resulted in a shift in assets under management into the project finance market. Credit enhancement products, such as the European Investment Bank’s (EIB) Project Bond Credit Enhancement (PBCE) pilot initiative and the subsequent Senior Debt Credit Enhancement programme has facilitated the flow of those assets into projects throughout Europe.

The EIB, through its use of credit enhancement products, can mitigate the more difficult risks associated with infrastructure projects in Europe, allowing the bond investor to evaluate and take on the risks and rewards elsewhere in the structure of the deal.

Its PBCE package, for instance, in the form of an unfunded subordinated loan, provided enough support to raise senior debt ratings of project bonds on certain deals by a couple of notches, thereby making the paper attractive to a wider investor base.

Investing in Europe is one thing but investing in the emerging markets comes with additional risks and, while there are existing products to help mitigate those risks, it is hoped that the Elazig Hospital deal may form the makings of a template to be replicated for targeted products in areas of the world crying out for infrastructure investment.

“The key problem for institutional investors is that they don’t understand these markets so well,” adds Maier. “And even with existing risk mitigation products it is difficult for them to price and appraise their investments. The Elazig deal is a first response to what the market told us.”

The deal was structured with the input of infrastructure investor Meridiam. “The structure is easy to understand and is credible, thanks to the rating,” says Maier. “It gives us the potential to crowd-in an investor base into project finance.”

Supporting package

The package was arranged in such a way that the bonds achieved a rating two notches above the sovereign. ELZ Finance, the issuer of the bonds, raised senior debt in late 2016 consisting of €83.1 million (US$88.4 million) A1A bonds due 2034; €125.3 million A1B bonds due 2036, benefiting from the multilateral credit enhancement package provided by Mulitilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA) and the EBRD, and €80.0 million unrated A2 Bonds due 2036.

The package was arranged in such a way that the bonds achieved a rating two notches above the sovereign. ELZ Finance, the issuer of the bonds, raised senior debt in late 2016 consisting of €83.1 million (US$88.4 million) A1A bonds due 2034; €125.3 million A1B bonds due 2036, benefiting from the multilateral credit enhancement package provided by Mulitilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA) and the EBRD, and €80.0 million unrated A2 Bonds due 2036.

On March 21, Moody’s affirmed the Baa2 rating even as it changed its outlook on the Turkish Ba1-rated sovereign to negative from stable. The package incorporates political risk insurance from MIGA, which brings with it the benefits of being a recognized global product. One that is standardized with transparent pricing.

“It gives the investor confidence in the outcome of any dispute. MIGA has a great track record,” says Maier. “The problem for institutional investors is that any potential dispute resolution process takes time. During that time they are not receiving coupons, and that is difficult for an institutional investor to justify.”

That is where the credit enhancement from the EBRD supports the structure. “The EBRD provided an unfunded, subordinated standby liquidity package over the construction and operating phases to keep debt payments current in case of construction overruns and the Turkish Ministry of Health missing payments,” says Christopher Bredholt, vice president, senior analyst at Moody’s.

“The on-demand liquidity is an important complement to the MIGA policy, which requires achieving an arbitral award against the government before claiming under the breach of contract cover, giving rise to a potential time lag in recovery,” adds Bredholt.

The enhanced rating also benefits from the availability-based revenue stream linked to the euro, thereby mitigating currency risk, and robust contracts from a country with a proven track record on delivering successful Public Private Partnerships (PPPs).

The package has worked in delivering institutional debt finance for Elazig Hospital in Turkey and the EBRD hopes it will show the way for other similar transactions. It certainly plans to use the scheme itself in other projects and countries. It is also keen to promote it as a product for project financing outside of its own remit.

Wider appeal

There is talk of the structure being replicated by MDBs in Latin America and Africa and it could play a useful role in some jurisdictions in Asia. But the region has its own dynamics to contend with.

There is talk of the structure being replicated by MDBs in Latin America and Africa and it could play a useful role in some jurisdictions in Asia. But the region has its own dynamics to contend with.

“Can the MIGA/EBRD scheme be transported to address the different risks in Asia?” asks Terry Fanous, a managing director at Moody’s in Asia. “Yes it can, but it’s difficult to generalize because the structure used was specific to Elazig, and Asia is a diverse region with different country specific dynamics. However, credit enhancement structures that include political risk insurance cover certainly have a role to play in Asia.”

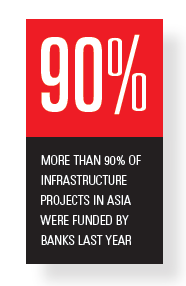

Infrastructure financing, in general, is hindered in Asia due to the region’s limited access to international capital markets and its underdeveloped domestic currency markets. Commercial and policy banks tend to dominate the sector.

“More than 90% of infrastructure projects in Asia were financed by the bank markets last year,” says Fanous. “Evolving regulatory frameworks, currency mismatch, information asymmetry and political risk are inhibiting appetite from institutional debt capital.”

That said, there are attempts in place to attract institutional investors into the region and the combination of political risk and liquidity facility could find employment in some areas.

Indonesia, for example, is one such country in Southeast Asia where it could work. The country has large infrastructure needs and is open to the PPP structure. Some of the projects also benefit from hard currency revenue streams, which would mitigate any foreign exchange concerns.

“This scheme has potential in Indonesia where issuing paper offshore might be required in order to finance projects,” says Sarvesh Suri, director of operations at MIGA. “We think bonds issued in dollars could find a home with investors in Singapore, for instance, where Indonesia risk is already well understood.”

Whether the scheme developed for Elazig finds a place in Asia any time soon is open to question, but the deal has created a template for other projects that can be easily replicated around the globe.

“The question is how best to use our balance sheet in order to leverage-in the private sector,” says Maier. “The future belongs to this type of risk management scheme.”

.jpg)

.jpg)